A good question is a thinking exercise

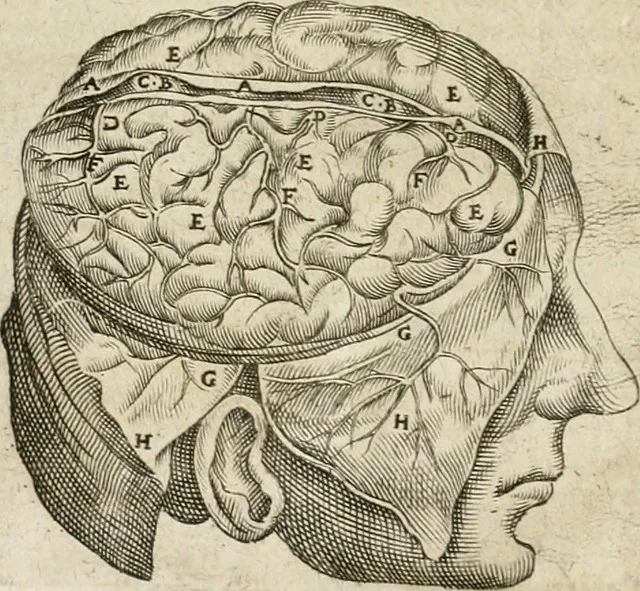

Who knows what’s in there? (Image credit)

The body of collective human knowledge has its origin in good questions.

Questions like “Does the sun actually revolve around the earth?” and “What will happen if I take a bite of this thing that looks like food?” have helped humans to develop an ever-advancing civilization.

At its core, science is a systematic framework for asking and answering questions and organizing the knowledge gained therefrom.

It’s tempting, when there’s a good question, to simply look up the answer. It’s never been easier to do so.

However, any opportunity for thinking is an opportunity for growth. Too many of us, when faced with a challenging question, are tempted to simply skim off the surface of our thoughts for the answer. I can simply put some words together that sound good without actually working that hard.

It’s much more challenging to access the deeper layers. If you haven’t spent much time doing it, it can feel impossible, like trying to climb up a boulder with a smooth face.

Kids deal with this feeling pretty straightforwardly. They say, “I don’t know,” or, “I give up,” or make random guesses.

Adults are more savvy. We say, “well, isn’t that a good question! You know, that reminds me of…” and then they’re off and running on a subject they know more about.

I learned a great deal about the power of good questions to stimulate good thinking (and learning) from Bernard Nebel’s Building Foundations of Scientific Understanding, a science curriculum for grades K through eight. Having made As in my honors high school and college science courses, I thought I know what was up. But Bernie’s work made me realize that I had a forest-for-the-trees problem. I knew a bunch of facts, but I didn’t see how they all fit together.

The BFSU curriculum is built around intriguing questions. A lot of these questions had an “everybody knows that” vibe to them until I dug deeper. For instance, “How does the body get energy?” seems very straightforward: You eat, you digest your food, you get energy and nutrients.

But how do the nutrients get where they are supposed to go, and what form is this energy in? Going even deeper, I realized that we’re talking about how every single cell of the body gets the energy and nutrients it needs to function. I had a lot of the puzzle pieces, but I wasn’t able to put them together until Nebel led me through this process of inquiry.

How could I have not understood the role of the blood in transporting oxygen and glucose, carbon dioxide and metabolic waste? But once I saw this clearly, I could easily reason through the function of virtually every other major organ in the body.

What was once a mishmash of facts and diagrams to be memorized for an exam is now a beautifully elegant process that I can not only reconstruct in my mind, but also share with someone else — ideally, by beginning with a question.

The scientific method that we all learn in school glamorizes the “hypothesis and experiment” part, but we use other parts of the scientific method constantly in our daily lives as we formulate questions and make observations.

Just as a child is eager for the chance to exercise her body when she encounters a well-designed playground, a particularly good question is a playground for exercising our thinking. Whether or not we are able to arrive at “the right answer” on our own, the time spent in deliberate practice of thinking is highly beneficial.

And every so often, like Copernicus or Newton or George Washington Carver, we may arrive at an insight that moves us all forward in our understanding and effectiveness as humans. You never know.